Shamrocks have long been a symbol of Ireland, and therefore

of Saint Patrick’s Day. It is important

to note the distinction between the shamrock, which has three leaves, versus

the lucky clover, that has four leaves. The

traditional story is that the shamrock was used by Saint Patrick as a symbol

for the Holy Trinity (the father, son, and Holy Ghost of the Christian

religion) in his attempt to convert the pagan Irish to Christianity.

|

| Statue of Saint Patrick located on the Croagh Patrick pilgrimage trail, County Mayo, Ireland. (Wikimedia Commons) |

Being the patron saint of Ireland, most people assume that he was Irish, he was not. He was a 5th century Roman Britain that was kidnapped and taken to Ireland as a slave at the age of 16. He later escaped to study in Britain and France only to return to Ireland as a missionary. It is believed that he died on March 17, 461 AD and that is why we commemorate Saint Patrick on that day.

As mentioned, the traditional story surrounding the importance

of the shamrock is due to its connection to Saint Patrick but there is evidence

that it has a much older significance to the pagan Celts and Druids. The importance of the idea of the number

three was not a new concept to the Celts.

They believed there was something very special about the number

three. This can be seen throughout their

iconography in the Triskele, the Triquetra or Trinity knot, the Serch Bythol,

the shamrock, and many more.

|

Entrance stone at Newgrange Neolithic site, Boyne Valley,

Ireland dating to c. 3,200 B.C. (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

The Triquetra or Trinity Knot also represents the

importance of three because it is created with one continuous line some also

believe it represents eternal spiritual life. (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

The Serch Bythol is made of two joined trinity knots and

to some beautifully represents the idea of eternal love between two joined

souls. (Wikimedia Commons) |

Just as the Christian tradition used the symbolism of three to represent the father, son, and Holy Ghost the pagan tradition attributed the importance of three to the goddess and her status as the maiden, mother, crone. Other meanings include the importance of land, sea, and sky or mind, body, and spirit, or underworld, middle world, and upper world.

|

| Pearlware teapot with hand painted shamrock decoration excavated from the Metropolitan Detention Center Site (36Ph91). (Collection of The State Museum of Pennsylvania) |

Though there are only a few, we do have at least one example of the shamrock design in our collection, as shown in this Pearlware teapot adorned in shamrocks. Miraculously, it was found whole, missing only a small portion of the lid. Pearlware is an earthenware that was developed in England in the 1790’s. Its most distinguishing characteristic is the slightly blue cast of the white glazed areas. Cobalt pigment was added to the glaze to produce a whiter glaze than the cream-colored glaze that was prevalent at the time. This cobalt tinge is often exhibited in the blue pooling on the base of the ceramic or in any grooves of the design. The production dates of pearlware are 1795-1820.

The teapot was recovered from a circular trash pit feature at the Metropolitan Detention Center Site (36Ph91) in Philadelphia. The feature layer containing the teapot also contained several other whole or near whole vessels. This suggests that the archaeological deposit was the result of a single occurrence or over a short period of time, such as an intensive cleaning episode, perhaps at the transfer of ownership of the property, or as the result of change in the popularity of the style of the vessels.

|

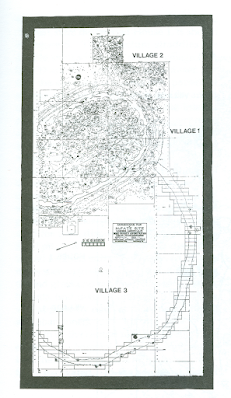

Picture of deposit layer of Feature 56 containing the

near whole vessels displaying the lid of the shamrock teapot in situ (36PH91).

(Collection of The State Museum of Pennsylvania) |

The property containing this site was part of William Penn’s original town of Philadelphia and this tract of land was patented in 1690. The site investigation by The Cultural Resource Group of Louis Berger & Associates included extensive historical research on the development of the site through the 19th century. This provided invaluable information about the various domestic and industrial activities of this period in Philadelphia’s history.

Since many become a

bit “Irish” on March 17th, we hope you have enjoyed this look back

at the origins of some of the traditions and artifacts commemorating a small

but significant island nation. We encourage you to visit the on-line

collections of the Pennsylvania

Historical and Museum Commission to see additional examples of

artifacts from Pennsylvania’s history.

References:

Louis Berger & Associates, Inc.

1997 Archaeological and Historical

Investigation Metropolitan Detention Center Site (36PH91).

Report to the U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of

Prisons, Washington, D.C.

Porter, Thomas H.

1857 The

Shamrock. Ulster Journal of Archaeology 5:12-20

Accessed 3/10/2022 – 3/15/2022:

https://www.history.com/topics/st-patricks-day/history-of-st-patricks-day

https://irisharoundtheworld.com/the-shamrock/

https://irisharoundtheworld.com/celtic-symbols/#beltane

https://irelandtravelguides.com/celtic-triskele-history-meaning/

https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/News/From-shamrock-and-rosettes-to-Patricks-Pot