While our current outreach is limited by social distancing

and travel bans, this week’s blog will focus on ways to explore the diverse and

rich archaeological resources of Pennsylvania from the comfort and safety of

home.

|

Petroglyph tour of

Pennsylvania. Image: PHMC

Petroglyphs Brochure

|

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), like many other public and private entities, has turned the negative of COVID-19 related museum and site closures into a positive opportunity to re-double efforts on long-term virtual access initiatives. The Commission as a whole has greatly increased available online exhibits, archives, and collections by adding new records and interactive web-based tools as part of our greater telework mission. We strongly recommend checking out our new and improved offerings, but we also want to share a handful of additional online resources produced by a variety of academic, professional, local non-profit, state and federal institutions.

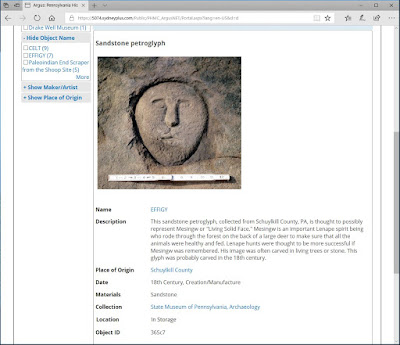

To begin our virtual tour of PA’s archaeological resources, we’d like to highlight the recent soft launch of an online Argus object search engine for The State Museum and Trail of History Sites and Museums. The Section of Archaeology has added new artifacts every week to this database during the office closure. To quickly access archaeological objects in the Search Collection tab, use the wild card symbol (*) with the keyword search term (*Archaeology*) or (*Archeology*). We further recommend taking a brief side trip on the Pennsylvania Trailheads blog of the Bureau of Sites and Museums. This week’s post has more information about the PHMC’s new collection search tool.

|

Archaeology Object

Search Example, Sandstone Petroglyph, Schuylkill County, PA

|

In addition to the Section of Archaeology’s bi-weekly blog, This Week in Pennsylvania Archaeology, and Sites and Museums, Pennsylvania Trailheads, the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) also posts updates on a regular basis in their equivalent forum, Pennsylvania Historic Preservation. Again, using the search term “Archaeology” or “Archeology” you can read more about on-going archaeological projects throughout the state. Here’s a link to an archived blog about Shawnee-Minisink, a National Registered Paleoindian and Archaic Period site in the Upper Delaware Valley moving your virtual travel to the northeast.

Following the Delaware River downstream, Philadelphia is a

treasure trove of history and archaeological resources. We recommend a visit to

the Philadelphia Archaeology Forum, a one stop shop of information, and the

Digging I95 interactive website administered

by AECOM in collaboration with the US Department of Transportation Federal

Highway Commission and the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDot).

Expanding the exploration beyond the

confines of Pennsylvania you can also visit the Penn Museum at the University

of Pennsylvania. Their Daily Dig series features a new artifact from their world-wide

collections every day during the coronavirus shut down. A virtual visit to Philadelphia

would not be complete without a stop at Independence National Park, Preservation-Archaeology.

Next, take a virtual tour of Pre-Contact archaeological heritage

districts through a PHMC Historic

Marker Search. Select a county and search category “Native American” to

discover prehistoric and Contact Period local cultural resources. We would

recommend heading west from Philadelphia to Lancaster County in southcentral,

PA. Pick a marker and enter the provided

GIS coordinates in google earth to get a birds-eye or street-view of locations

marking the former village sites of the Susquehannock and other Native American

groups that lived along the Susquehanna River.

|

PHMC Historical Marker

Search Example

|

You can continue your virtual journey through the Susquehannock Native Landscape at The Zimmerman Center for Heritage. Part of the Susquehanna National Heritage

Area, this National Park Service (NPS) cultural center serves as the Trailhead

of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National

Historic Trail,

another resource worth exploring. Video content on the site allows you to fly

over the Susquehanna River from Columbia Crossing to the Zimmerman Center.

Then check

out other local history venues with archaeological collections using the

museums’ listing links on the archived PHMC Pennsylvania Archaeology website.

|

PHMC Pennsylvania

Archaeology

|

Not listed in the PHMC guide is the new home of the

Westmoreland Historical Society, Historic Hanna’s Town. This

site takes our tour west of the Allegheny Mountains to a frontier town,

established in 1773 by the British colonial government. Hanna’s Town played an

important role in the American Revolution and was burned down by a Seneca

raiding party in 1786 towards the end of the conflict. It’s reclamation from

early Republican county seat to farmland in the early 19th century

encapsulated in the archaeological record a turbulent time in our country’s

history.

To read more about recent archaeology conducted at the Hanna’s Town, follow

Ashley McCuistion’s blog, Digging

Anthropology, tales from the sandbox. This is an archived website dedicated

to her Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP) graduate student investigations

at the DuPont Powder Mill site, Fayette County, PA; field schools at Hanna’s

Town, Pennsylvania and Ferry Farm, Virginia; and undergraduate work with the Virtual Curation Laboratory

(VCL) at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU).

|

Dr. Bernard Means 3-D

scanning turtle carapace, Image: The State Museum of Pennsylvania, Section of

Archaeology Collections.

|

Incidentally, VCL’s director, Bernard Means, has worked

extensively with archaeological collections held at The State Museum of Pennsylvania,

primarily from Monongahela Village sites in Somerset County. His research has

been featured in our past blogs about Somerset County and Sharing and Preserving

the Archaeological Record.

IUP also has a dedicated

archaeology blog that is regularly updated, Trowels and Tribulations, that is worth a view.

Continuing in Southwestern Pennsylvania, you can visit the

earliest documented archaeological site in North America, Meadowcroft

Rockshelter and Historic Village in Avella, Washington County. The park and

several other museums in the greater Pittsburgh metropolitan area are

administered by the Senator John Heinz History Center. The History Center’s online

offerings are outstanding and include many interactive ways to explore its exhibit

and site holdings.

The Fort

Pit Museum in downtown Pittsburgh, part of the PHMC Trail of Military History, is also administered by the Heinz

History Center. The site has a long history of archaeological conservation and

investigation through the efforts of The Fort Pitt Society of the Daughters of

the American Revolution. Visit the Fort Pitt Block House

website for more information about past excavations and additional interactive

resources.

Here are a few resources to help you turn this tour into a

virtual family vacation. The National Park Service (NPS), Educator

Resources, and the Society for American Archaeology (SAA), Teaching Archaeology, websites have a number of options

for those of us struggling to find creative ways to engage our school-aged kids

during stay-at-home orders. Heading back southwest to Cambria County, the NPS

has Kindergarten through Sixth grade lesson plans for the Johnstown Flood

National Memorial. Or you can travel back in time across central Pennsylvania

on the historic Allegheny Portage Railroad which connected the Midwest to the

eastern seaboard between 1834 and 1854.

Finally, you can round out your experience at a virtual

excavation with the Archaeological Institute of America and Archaeology magazine’s

interactive digs. None of the available

excavations are located in Pennsylvania, but it’s worth mentioning as a fun way

to cap off our tour.

Most of us are itching to get on the road and have a change

of scenery after two months of quarantine. The global pandemic has given us all

opportunity to reflect on what we value and how an understanding of our past

can help us better plan for the future. It is still safest to stay home and

follow recommendations of Governor

Wolf and the CDC. A few PHMC sites are moving from red to yellow phase

restrictions in the northwest and northcentral health districts at the end of

this week. Drake Well Museum and the Pennsylvania Lumber Museum are in the

planning stages of re-opening their grounds, but not their facilities, to

visitors soon. Please continue to visit online resources and call ahead for

up-to-date COVID-19 health and safety restrictions as part of any travel plan

in the near future. In the meantime, we hope you are able to fulfill some of

your curiosity and wanderlust with a few of our recommendations for travel down

a virtual archaeological rabbit hole or two.

Online Resources

AECOM

2014 Home Page, Digging I95. November

14, 2014. https://diggingi95.com/.

Archaeological

Institute of America and ARCHAEOLOGY magazine

2019 Interactive Digs. https://www.interactivedigs.com/

Bureau of

Historic Sites and Museums (PHMC)

2020 Curating from Home, Pennsylvania Trails

of History Trailheads. Blog Post, May 8, 2020.

Bureau of

The State Museum of Pennsylvania (PHMC)

2017 Home Page, http://statemuseumpa.org/.

Bureau of

The State Museum of Pennsylvania, Section of Archaeology (PHMC)

2013 Somerset County, This Week in

Pennsylvania Archaeology. Blog Post, August 16, 2013.

2018 Sharing and Preserving the

Archaeological Record, This Week in Pennsylvania Archaeology. Blog Post,

August 13, 2018.

Fort Pitt

Society

2020 Fort Pitt Block House, Archaeology. http://www.fortpittblockhouse.com/archeology/

Indiana

University of Pennsylvania, Archaeology

2020 Trowels and Tribulations: IUP’s

Archaeology Blog. http://iblog.iup.edu/trowelsandtribulations/

McCuistion,

Ashley

2016 Digging Anthropology, Tales from the

Sandbox. Blog, last post January 22, 2016. See Hanna’s Town. https://diganthro.wordpress.com/; https://diganthro.wordpress.com/hannas-town/

National

Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

Educator Resources, Pennsylvania,

Archaeology, https://www.nps.gov/teachers/teacher-resources.htm?#sort=score+desc&q=Pennsylvania,+Archaeology

2016 Independence National Historical Park,

Pennsylvania. Archaeology at Independence. September 6, 2016. Learn

About Park, History & Culture, Preservation, Archaeology. https://www.nps.gov/inde/learn/historyculture/preservation-archeology.htm

2019 Captain Johns Smith Chesapeake National

Historic Trail, VA, MD, De, DC, PA, NY. March 12, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/cajo/index.htm

Penn Museum

2019 Events, Adult Programs, The Daily Dig. https://www.penn.museum/events/adult-programs/the-daily-dig?utm_source=collections&utm_medium=webpage&utm_campaign=homepage

Pennsylvania

Department of Health

2020 Health, All Health Topics, Disease &

Conditions, Coronavirus. https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/coronavirus/Pages/Coronavirus.aspx

Pennsylvania

Historical and Museum Commission,

2015 Pennsylvania Archaeology, Resources,

Museums and Tours. September 10, 2015. http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/archaeology/resources/museums-tours.html

Petroglyphs Brochure, pdf. http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/archaeology/files/petroglyphs.pdf

2020 Home Page, https://www.phmc.pa.gov/Pages/default.aspx

Marker Search, http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/apps/historical-markers.html

Trails of History, https://www.phmc.pa.gov/Museums/Pages/default.aspx

Military Trail of History, https://www.phmc.pa.gov/Museums/Military-History/Pages/default.aspx

Museum Collection, Search Collection,

Archaeology, https://5074.sydneyplus.com/Public/PHMC_ArgusNET/Portal.aspx?lang=en-US&d=d

Pennsylvania

State Historic Preservation Office (PHMC)

2020 Pennsylvania Historic Preservation, Blog

Homepage. https://pahistoricpreservation.com/

2014 Spotlight Series: The Shawnee-Minisink

Archaeological Site. Pennsylvania Historic Preservation. Blog Post, March 12, 2014. https://pahistoricpreservation.com/shawnee-minisink/

Philadelphia

Archaeology Forum

2020 Home Page, https://www.phillyarchaeology.net/

Sea Grant

Pennsylvania, The Pennsylvania State University

2016 The Pennsylvania Archeology Shipwreck and

Survey Team (PASST). https://seagrant.psu.edu/topics/projects/pennsylvania-archeology-shipwreck-and-survey-team-passt

Senator John

Heinz History Center

2019 Exhibits, Meadowcroft Rockshelter. https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/exhibits/meadowcroft-rockshelter

Fort Pitt Museum, https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/fort-pitt/

Society for

American Archaeology

2020 Education and Outreach, K-12 Activities

& Resources. https://www.saa.org/education-outreach/teaching-archaeology/k-12-activities-resources

Susquehanna

National Heritage Area

2020 River History, Susquehannock Native

Landscapes. https://www.susquehannaheritage.org/discover-river-history/susquehannock-native-landscape/

Thomas T.

Taber Museum

2020 Explore the Museum, American Indian

Gallery. https://tabermuseum.org/explore-museum/american-indian-gallery

Tioga Point

Museum

2019 Collections. https://www.tiogapointmuseum.org/collections

Virtual

Curation Laboratory, Virginia Commonwealth University

2015 Discoidal from Peck 2. Virtual Curation

Museum. Blog Post September 18, 2015. https://virtualcurationmuseum.wordpress.com/

Westmoreland

Historical Society

2018 Home Page, Historic Hanna’s Town, https://westmorelandhistory.org/hannas-town

For more information, visit PAarchaeology.state.pa.us or the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania .