Friday, December 2, 2016

LiDAR Aids Archaeologists in Documenting Fort Hunter

Friday, August 1, 2014

Jefferson County Revisited

References:

Raber, Paul A.; Scott D. Heberling; Frank J. Vento

(2012) Phase I Archaeological Survey S.R. 3007 Section 550; Summerville Bridge Replacement Summerville Borough, Jefferson County, Pennsylvania

Yeoman, R.S.

(2001) A Guide Book of United States Coins, 54th Ed. St. Martin's Press, New York

Friday, December 2, 2011

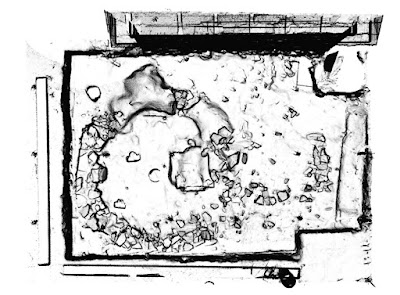

Dyottville Glassworks

Down by the river (please excuse the Chris Farley reference) and a stone’s throw away from whizzing interstate traffic, a team of archaeologists from URS Corporation, lead by Doug Mooney, have uncovered the remains of an important part of our nation’s emerging industrial might of the 19th Century, the Dyottville Glass manufacturing complex along the Delaware River.

Not surprisingly due to its proximity to the Delaware River, prehistoric artifacts such as triangular projectile points and fragments of native-made pottery dating to the Late Woodland period were discovered at the site underneath the multiple layers of historic occupation.

During the visit, it was noted that with a great deal of attention being focused on archaeological investigations that have taken place near Center City (in association with Independence Hall, the National Constitution Center, and President Washington’s house, etc.), residents of the somewhat removed Kensington and Fishtown neighborhoods of the city have taken a measure of pride in a piece of their own heritage discovered just a few blocks from their doorsteps. Yo!

Click here for an article that Hayden Mitman wrote for the Northeast Times about an artifact exhibit at the Kensington CAPA High School, and here for a more in-depth overview of Dyottville by Ian Charlton of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania for Philaplace.org.

Friday, November 19, 2010

Compliance Archaeology

These are some of the typical questions we hear from people not familiar with the state of archaeology as its practiced today in Pennsylvania and across the nation. It is a difficult task to fully explain the context in which the majority of archaeology these days takes place in the span of a 700 word or so blog post, but it is important stuff so we’re taking a stab at it anyway. We’ve touched on this topic in several previous posts so if you have the time we encourage you to do a little “digging” through the TWIPA archives.

Most archaeology today is conducted prior to some type of development; roads, bridges, housing subdivisions, dams, prisons, railroads, post offices, courthouses, pipelines – you get the idea. All of these projects have the potential to disturb or destroy archaeological sites. Fortunately, Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 created a framework as part of any federal undertaking by which sites can be identified, evaluated, and if warranted, destructive activities mitigated. In a nutshell NHPA acknowledges that it is in the best interest and to the benefit of the American people (current and future generations) that significant cultural resources, historic and prehistoric, be documented and preserved where possible. It also recognizes that federal agencies have a responsibility to take into account adverse effects their development projects may have on these significant cultural resources. If this is beginning to sound like contorted legal mumbo jumbo, we apologize, but that’s what it is.

While the artifacts themselves are the property of the landowner on whose land the site was excavated, in Section 106 projects the information recovered, the data (the field forms and notes, artifact inventories, photo documentation and reports) is owned by all of us, as we the taxpayers are ultimately footing the bill for not only the development but also the preservation efforts.

More often than not, the landowner understands the artifacts have more scientific value than they do monetarily, and generously donates them to the State Museum where they are incorporated into a comprehensive database and made available to researchers the world over for a wide variety of scholarly studies, as loans to local historical societies, and of course permanent and temporary exhibits both large and small in the Anthropology and Archaeology Gallery of the State Museum, as well as other historic sites administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

One common criticism directed towards archaeologists is that results from these excavations are not shared with the public often enough or in a timely manner. Doing our bit to dispel this shortcoming, we’ve contacted some good people at PennDoT, and they were all too happy to pass along a link to popular publications here , resulting from transportation projects. The page is a little buried, then click "kids page" and then click "highways to archaelogy".

This week we’re highlighting a few of the unsung heroes of Cultural Resource Management (or CRM for those readers who don’t have enough acronyms in their life) the archaeological foot soldiers in the trenches, literally, doing battle with deadlines on compressed time tables, emaciated budgets and inclement weather – just to name a few typical obstacles. While we can’t claim these woes, or any others for that matter, are bedeviling this particular project, its recent appearance in the news seemed to make it a timely and appropriate example of Pennsylvania CRM archaeology. Currently underway is a road re-alignment near the borough of Macungie in Lehigh County, and people are curious and asking questions, and that makes it the perfect opportunity for the archaeology community to engage the public and hammer home the message that archaeology is good for them.

For more information, visit PAarchaeology.state.pa.us or the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania .

Friday, July 2, 2010

Celebrating Independence Day

Friday, October 23, 2009

Archaeology Day at the State Capitol

To quote from the SPA web site on the value of archaeology:

“Men, women, and children have lived in the Commonwealth for nearly 14,000 years. Yet only a small portion of that time is documented on paper. Archaeological evidence often represents the only surviving record of Pennsylvania’s prehistory and can provide new information about where, when and how these people lived in the past”

We might add that this information can also be used to improve our own future.

At noon, there will be a ceremony for the John Stuchell Fisher Award. This is given in recognition to local, state and national officials who contribute to the promotion and understanding of archaeology in Pennsylvania. This year’s recipient is Mark Platts, President of the Susquehanna Gateway Heritage Area. He is receiving this award for efforts in preserving archaeological resources in Lancaster and York counties. Of special significance is his successful initiative to preserve the last two villages occupied by the Susquehannock tribe in the 17th century prior to their demise in the region. Steve Warfel, former Senior Curator of Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania will comment on the significance of this work. The speakers will begin at 12:00.

Archaeologists from the Section of Archaeology of The State Museum and the Bureau for Historic Preservation will represent the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. The Section of Archaeology serves as the primary repository for archaeological collections and holds over four million archaeological specimens in trust for the citizens of Pennsylvania. They are also responsible for the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology in the State Museum which provides a comprehensive tour of Pennsylvania archaeology from the Paleoindian period through the 19th century. On display at the Capitol will be a spectacular array of artifacts from sites in York County reflecting the Susquehannocks involvement in European trade.

Of particular interest to the younger generation, the Pennsylvania Archaeological Council and Indiana University of Pennsylvania will put on a demonstration in the early afternoon on Native American technology. For nearly 14,000 years, people lived in Pennsylvania without factories, automobiles or convenience stores. They used a relatively simple technological system to get their food, to make their clothing and obtain all of their material needs. Tying and attaching things with string and rope was a very common activity and essential to their lives. Everything from bow strings to fishing nets was necessary but where did they get the yards and yards of cordage to make these items? Cordage in Native American cultures was like duck tape is to our culture. The children visiting the exhibit will be invited to try their hands at making cordage and using a prehistoric drill. Think of all of the holes that need to be drilled into items to make them functional. This event will begin at 12:30.

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation also has an active archaeology program. As part of their environmental stewardship program, they endeavor to protect archaeological sites that may be affected by their construction projects. For decades they have been conducting archaeological investigations prior to construction and they have recovered significant information on past cultures in Pennsylvania. They have developed a publication series and examples will be available, including their most recent publication on the archaeology conducted along the route 11/15 corridor.

The Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology will have an exhibit describing the variety of activities they conduct around the Commonwealth to enhance and protect archaeological sites and artifacts. The local chapter, Conejohela Chapter 28, will have an exhibit presenting their involvement in preserving the Susquehannock sites in the lower Susquehanna Valley.

Friday, August 28, 2009

The Trouble with Historians and Archaeologists: Auditing the Frankstown Branch Bridge Replacement

Block 2, crew shot

Even the smallest archaeological find can yield rewarding information for a historian. The Phase I and Phase II Archaeological Surveys on this bridge project south of Hollidaysburg on Rt. 36 only dug up 107 artifacts that ranged from historic pottery to prehistoric chert flakes to chert tools. Just like historians, archaeologists rely on the evidence they find, and they then interpret whatever evidence that is found. At the Frankstown Branch site the artifacts showcased a small prehistoric task group or nuclear family group that subsisted by practicing a hunter/gatherer system. The site also contained entirely local resources and features, which bent the analysis toward the site being used by a small band from a local community.

Test Unit 2, west profile

The analysis on the social aspects of the site constituted important as well as usable information to any social historian investigating native cultures. This is the interesting point. This very small fraction of archaeological information can shed light on social habits that historians might set their sights on when investigating local prehistoric communities and their social makeup.The trouble with historians and archaeologists is they forget what they have in common. When it comes to interpreting the past, historians and archaeologists are slaves to what they find. We are governed by it. If together we work to combine the soiled and written evidence, perhaps we can arrive at a clearer concept of the past. This new vantage point can then serve as a springboard for better management of our resources regardless of location in reference to the ground.

Shovel Test excavation

Lastly, this historian must thank the Section of Archaeology at the Pennsylvania State Museum for the opportunity to work with them. Thanks, Janet, Andrea, Liz, Dave and Dr. Carr.

For more information, visit PAarchaeology.state.pa.us or the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania .Friday, August 14, 2009

Summer 2009 Internship Section of Archaeology

My name is Thomas Wambach and I am an Anthropology/Archaeology major at Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), about to enter my junior year. This summer, I participated in an internship with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), Archaeology Section located in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. I received this internship via the Diversity Internship Program, whose goal is to increase staff cultural diversity in Pennsylvania’s museums and cultural organizations. As I am of Haitian American ancestry, I found the program to be captivating as well as a worthwhile experience. It certainly has increased my knowledge of archaeology outside the classroom by helping me learn in a professional environment, under a well qualified mentor in my field.

My name is Thomas Wambach and I am an Anthropology/Archaeology major at Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), about to enter my junior year. This summer, I participated in an internship with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), Archaeology Section located in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. I received this internship via the Diversity Internship Program, whose goal is to increase staff cultural diversity in Pennsylvania’s museums and cultural organizations. As I am of Haitian American ancestry, I found the program to be captivating as well as a worthwhile experience. It certainly has increased my knowledge of archaeology outside the classroom by helping me learn in a professional environment, under a well qualified mentor in my field.As an intern in the Archaeology Section, I accomplished a number of personal and professional goals, and worked on a variety of different tasks and projects. My main project of focus during the internship was the processing of a collection of artifacts from an archaeological site in Clinton County, Pennsylvania known as the West Water Street Site (36 CN 175), located in Lock Haven, and excavated in 1992 by students from the University of Delaware. This was a stratified prehistoric site spanning nearly the entire time span of human occupation of the Susquehanna Valley. The artifacts I worked with dated to the Pre-Middle Archaic, Middle Archaic, and Late Woodland periods of human occupation in Pennsylvania. The first project task involved using printed records of the site’s artifacts, provided by the University of Delaware, to reenter data on artifacts spanning the first section of archaeological excavation at the West Water Street Site into an electronic database. An electronic database was unavailable from the University of Delaware for various reasons.

Once this section of the database was reentered and using a printed spreadsheet of the artifacts’ locations, I began to pull artifacts, by catalog number, from their original “pizza box” shaped cardboard boxes in one of the collection holding rooms occupied by the Section of Archaeology so that I could re-house these artifacts. That is to say, I pulled artifacts with catalog numbers 1200, 1400, 1500 etc, and re-housed them with their correct provenience information in larger acid free cardboard boxes. This encompassed a majority of the work I accomplished with the West Water Street Project, and represented a continuation of work performed by previous interns in the Section of Archaeology. The project was initially difficult, because many of the artifacts were scattered among a multitude of boxes in no particular order. Hence, finding the correct artifact was not only tedious, but also presented the possibility that certain artifacts might be missing from their original box. Overall, I estimate that more than four hundred bone, stone, ceramic, and FCR (fire cracked rock) artifacts were pulled and re-housed during my time here.

My time with the Section of Archaeology, however, was not simply limited to this activity. I also attended intern seminars held every Friday by Penn DOT’s Bureau of Design, Cultural Resources Section’s own Mr. Joe Baker. These seminars were organized and designed in a manner similar to a class lecture and discussion course to teach interns valuable lessons on historical preservation in Pennsylvania and the rest of the country, especially by introducing the rules and regulation of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

Other additional duties included the re-housing of artifacts outside my specific major project activity, and checking climate controls (temperature and humidity) in all artifact collection rooms. During the latter activity, I discovered that dehumidifiers are fickle little machines! I also briefly participated in field work at an archaeological site near Millersville, which was a good way for me to review the excavation and field training skills I’d learned during the summer of 2008 during IUP’s field school course. Moreover, from time to time, I assisted staff in maintaining the museum exhibits and galleries in the State Museum and Archives areas. This activity allowed me to visit the museum, that I had frequented as a child. I also attended an archaeology conference that took place in Harrisburg and I learned, first hand, how the museum receives new artifacts from public and private institutions, as well as donors from across the Commonwealth.

My summer internship also provided me the opportunity to show off my skills as an artist by drawing a reconstructed stone core artifact for one of my colleagues. I certainly hope the sketch proves useful in the future. I also took part in field trips to other museums in the state and to sites under protection by the National Register of Historic Places to evaluate their techniques of reaching the public as well as in artifact and site preservation, all the while comparing my observations with those services provided by the State Museum. In addition, I took part in a small public outreach activity by answering a letter sent by someone who had special interest in local archaeology. I provided the client with resourceful online and book sources so that his research could be completed. Despite the fact that the client was writing from prison, the effort demonstrates that archaeology is for everyone, and that we [archaeologists] are humble public servants.

Most importantly, I established contacts and friendships with the staff here in the PHMC, which I hope will help me in the future. My time here was very educational, fun, and an otherwise memorable experience that I will value greatly. I recommend contacting, interning, or communicating with the PHMC to anyone who is studying archaeology, like me, or to those who are interested in archaeology and/or prehistoric and historical preservation. It certainly proved to be an integral and priceless education and experience for me!

Thank you to all my friends and staff from the PHMC!

For more information, visit PAarchaeology.state.pa.us or the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania .

Friday, July 24, 2009

Wayne County Emergency Bridge Replacement Project

Background research revealed the long and interesting history of the house and farm on the Eldred Site. A deed shows the area was originally surveyed by a man named Thomas Craig around 1811, but the farm was established in the mid-19th century by Judge Nathaniel Baily Eldred. A native of New York State, Eldred made quite a life for himself in Pennsylvania where he was elected to State Legislature and served for four years between 1822 and 1827. He was subsequently appointed to several important positions: Commissioner of the Milford & Owego Turnpike; president judge of the Eighteenth Judicial District and later of the Sixth Judicial District; and naval officer in the Philadelphia Customs House. He served a term as Canal Commissioner and was a member of the Board of Commissioners overseeing navigation of the Delaware River. He declined a nomination to the Supreme Court in 1851. Additionally, a township in Jefferson County was named in his honor.

Upon retiring and settling fulltime at his dwelling in Bethany Borough, Eldred and his wife conveyed the Eldred Farm to a man named Justus Sears who then sold it to German immigrant George Fogel by 1860. Fogel ran the 130-acre general farm on the site for a short time before assigning the property to Joseph Gerher. Over the next several years the property was assigned to William W. Sherwood and then to Henry Greiner, a Civil War veteran who had lived the life of a farmer before enlisting in Company H of the Fifty-Second Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in 1861. He participated in 1862 battles at Lee’s Mills in April; Seven Pines and Fair Oaks in May, Bottom Ridge and White Oaks Swamp in June, and Carter’s Hill in July. After the war Greiner owned and operated the Eldred Farm with his wife and two daughters for seventeen years before conveying it to James P. O’Neill and his wife Mary, but these new owners maintained their residence in Mount Pleasant Township and conveyed the Eldred property to a Pennsylvania-born farmer named Phillip H. Kennedy, Sr. shortly thereafter. Kennedy died in 1918, and in 1920 his wife conveyed the property to Henry Mead who ran it as a dairy farm until his death in 1961. The Eldred property is now in the hands of Henry’s son, Clyde E. Mead and family.

Friday, July 10, 2009

Carley Brook Bridge Replacement Project

Our blogger this week is Wes Stauffer an intern for the Cultural Resources Section of the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. Wes worked for a day in the Section of Archaeology observing our processes and auditing a Cultural Resource Management collection for compliance to our Curation Guidelines.

Under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, federal projects require planning and cooperation, in addition to hard work. This proved true when the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation determined that the Bates Road/Weidner Road Bridge over Carley Brook, near Honesdale in Wayne County, needed to be replaced. Built in 1916, it had fallen into a state of disrepair over time. To insure that no important cultural sites were destroyed by the construction of a new bridge, a site survey preceded any site work.

Ideally, background research as well as on-site surveys will locate any important historic and archaeological sites in the area of probable effect (or the area to be impacted by the footprint of a new construction project). Such surveys prove especially important along waterways. Waterways provide food and transportation routes today just as they did for our predecessors. Relatively level, well-drained soils adjacent to water travel routes, as well as the fertile soil in adjoining floodplains, provided prime locations for Native American camps and settlements.

At the Carley Brook site, research and archaeological investigation uncovered a portion of the former Staengle property. Leonard Staengle built a house on the property around 1889, as well as a barn and a butcher shop. Staengle cleared the land and established a small farming operation to supplement his butchering business. Various occupants utilized the property through to present day.

Archaeologists excavated no prehistoric artifacts from the area of probable effect. Approximately 85% of the 302 historic artifacts unearthed reflect kitchen or architectural usage. Research determined that the artifacts reveal an occupation period between the 1890s-1920s, however they were uncovered in a mixed or disturbed context. Furthermore, no building foundations were located. Archaeologists concluded that a former refuse dump lies within the area to be impacted by the construction of a new bridge.

With their research completed and archaeological evidence analyzed, archaeologists felt confident that construction of the new bridge over Carley Brook could proceed without negatively impacting any important cultural resources. All artifacts, donated to the Bureau of the State Museum of Pennsylvania, have been inventoried and archived where future researchers can study them and other artifacts like them.

Cultural resources management, integral to projects such as the Bridge Replacement project over Carley Brook in Wayne County, preserves our heritage and gives residents of Pennsylvania a better understanding of our state’s past communities as well as those individuals who lived and worked within them.

For more information, visit PAarchaeology.state.pa.us or the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at The State Museum of Pennsylvania .