During

the early nineteenth century, conflict between England and France led to an

American trade embargo that restricted the importation of goods from these

countries. Soon after, English hostilities on the high seas that led to the War

of 1812 also stopped the flow of foreign goods to America, including fine

British ceramics. The lack of certain imported goods led to the establishment

of a number of new American industrial enterprises to fill the void.

In

the late 1700s and early 1800s, a form of thin, cream-colored ceramic called

creamware was being manufactured in England. One style of creamware was made

popular by British Queen Charlotte and became known as Queensware. Queensware

enjoyed immense commercial popularity and was one of the items banned during

the embargo and subsequent war.

Creamware Cup (left)

Shown with a Copy in American Queensware (right)

Utilizing

local clays, some possibly dug from within the city, Philadelphia potters

attempted to make their own versions of Queensware and other fine British

earthenware ceramics. However, the use of local clays produced a more yellow

vessel body rather than white or cream colored. Some potteries, such as the

newly-formed Columbian Pottery, offered a British-trained potter to make the

enterprise seem more authentic. By 1808, Scottish-born Master Potter Alexander

Trotter was producing earthen tablewares for the Columbian, including yellow

tea and coffee pots, sugar boxes, jugs, baking dishes, chamber pots, and other

items. The Columbian’s goods were advertised “at prices much lower than they

can be imported” and at rates that “are less than half the price of the

cheapest imported Liverpool Queensware” (Myers 1980).

AMERICAN

Manufactured

Queensware, at the following reasonable

rates-viz

Chamber

Pots 4s a $2 25 per doz

Ditto

ditto 6s 1

80 ditto

Wash

Hand Basons 4s 2

ditto

Ditto

ditto 6s 1

60 ditto

Pitchers 4s 2

70 ditto

Coffee

Pots 4s 5 ditto

Ditto

ditto 6s 4 ditto

Tea Pots 12s 2 25 ditto

Ditto 18s 1 80 ditto

Pitchers 6s 1 80 ditto

Dinner

Plates 75 cents per dozen-all other sizes, with every other article of

Queensware, in proportion

Copied from a Price

List for Columbian Pottery Wares in Relfs

Philadelphia Gazette and Daily Advertiser 1813

Philadelphia Queensware

Pitcher and Teapot from PHMC Collections

Trotter’s

wares became popular and were soon advertised for sale as far away as

Alexandria, Virginia and other cities along the east coast. Trotter continued

his work in Philadelphia until around 1815, when the Columbian Pottery closed

up and he moved to Pittsburgh. For a short time period Trotter continued

manufacturing Queensware in the Pittsburgh area, where he produced vessel forms

that were “similar to those of the Potteries in Philadelphia” (Myers 1980).

By

1810, another Scotsman, Captain John Mullowny, was advertising similar ceramic

articles for sale at his Washington Pottery on Market Street. Mullowny also

appears to have been successful in his ventures and by 1812 he had added specialized

production techniques and included engine-turned and press-molded Queensware

vessels in his inventory (Myers 1980). An advertisement from that same year

lists the many vessel forms produced by the Washington Pottery (Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser

1812).

WAREHOUSE

OF THE

WASHINGTON

POTTERY,

HIGH NEAR SCHUYLKILL SIXTH

STREET,

The public are informed that

Soup and Shallow

PLATES are now ready for delivery in addition to the

following articles, of which a constant supply is always

kept up.

CUPS & SAUCERS,

SUGARS & CREAMS,

Gallon, Quart, Pint & Half Pint Grelled & Plain PITCHERS

Gallon, Quart, Pint and Half Pint BOWLS,

SALT and PEPPER BOXES,

STEWING DISHES that will stand the fire,

BASINS and EWERS,

WINE COOLERS,

MANTLE ORNAMENTS & GARDEN POTS

Quart, Pint and Half Pint MUGS,

GOBLETS, TUMBLERS & EGG CUPS,

BUTTER TUBS & BUTTER BOATS,

PICKLING JARS & JELLY POTS of all sizes,

MILK PANS, &c, &c, &c.

The Plates manufactured at the

Washington Pottery,

will be found by experience superior to imported plates,

when necessary to stew on a chafing dish or embers, as

they will stand the heat without cracking.

1812

Ad Copied from a Philadelphia Aurora

General Advertiser for the Washington Pottery

Following

the end of the war in 1815, many of the potteries continued to manufacture Queensware

vessels; however, the resumption of trade with Britain meant that the finer

quality Staffordshire wares were available once again and at rates similar to

the American-made knock-offs. Ceramics, as well as other British goods, flooded

the market in 1815 and 1816 in an attempt to stifle the new American industries.

Soon it became apparent that the Philadelphia potters could not compete with

England’s finer pieces and most of the Queensware producers were out of

business by 1820.

The

State Museum collections house a number of examples of Queensware recovered from

archaeological sites located mainly in the city of Philadelphia. Evaluation of

these pieces indicates that the quality of the Philadelphia wares is somewhat

lacking. Many issues related to the Queensware pieces appear to be associated

with the production and firing of the vessels including: overfired, burned, or

bubbled glaze; kiln furniture marks; uneven or missing glaze; crazing; smeared

clay; and pitting. Every piece identified as Queensware exhibited at least one,

if not several, of these flaws.

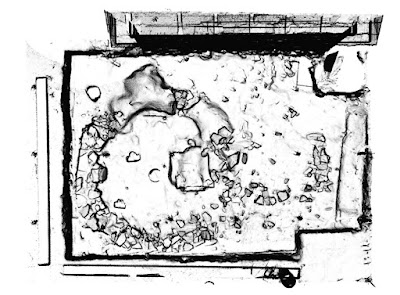

Closeup of Queensware

Cup Showing Cracking and Missing Glaze (Center Top) and Speckling

If

you found this blog of interest and would like more detailed information,

articles regarding Queensware will be published in an upcoming issue of The Journal for Northeast Historical

Archaeology. Additional information on Philadelphia ceramics and citations

for this blog can be found in the following sources:

Miller,

George L. and Amy C. Earls

2008 War and Pots: The Impact of Economics and

Politics on Ceramic Consumption Patterns. In Ceramics in America 2008.

Myers,

Susan H.

1980 Handcraft

to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century.

Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, No. 43. Washington: Smithsonian

Institution Press.

Philadelphia Aurora General Advertiser

1812 October 27.

Relfs Philadelphia Gazette and Daily Advertiser

1813 April.