The signature characteristics of various pottery forms are important for archaeologists in identifying the culture groups who created them. Our ability to trace the movement of pottery across the landscape aids in our understanding of settlement patterns and individual cultural groups known only to prehistory. Let’s examine some possibilities once again by visiting the Ohio River Basin (July 2, 2021 blog) where we can learn more about the interesting pottery types of the Late Pre-Contact period.

The Late Pre-Contact (AD.1050-1590) period in this region of the Upper Ohio Valley extends from Lake Erie southward through the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau Section of west central Pennsylvania drained by the Allegheny River system and the Unglaciated Pittsburgh Low Plateaus Section drained by the Kiskiminetas/Conemaugh River system (Figure 1). Most of the sites associated with Late Pre-Contact pottery types from these localities were temporary hunting and fishing camps and the permanent settlements of the McFate and Chautauqua cultures (Dragoo 1955; Mayer-Oakes 1955; Lantz and Johnson 2019; Schock 1974).

|

| Figure

1. Physiographic/drainage map of the western Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania DCNR) |

A hallmark defining these pottery types of the Late Pre-Contact period was the potter’s preferential use of crushed freshwater mussel shell as a binding or tempering agent added to the clay as opposed to the use of crushed rock temper in surrounding regions. Only rarely was rock temper used by the potters of the Late Pre-Contact period under discussion. The shell temper is most always finely crushed and never chunky like the marine oyster shell tempers of the coastal groups of the Northeast and Middle Atlantic regions.

|

Figure 2. Examples of decorative motifs on McFate Incised pots.

(After Lantz and Johnson 2020: Figure 12.9) |

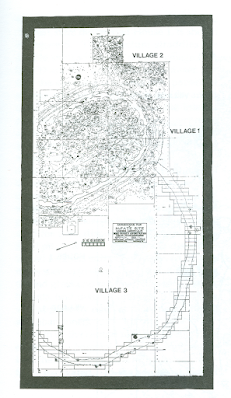

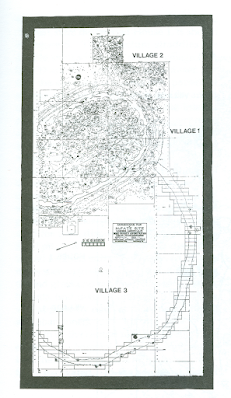

The first pottery type that we are going to describe is McFate Incised. McFate Incised is a pottery type with Iroquoian decorative elements involving a variety of incised line motifs on the lips and collars of collared and non-collared vessels (Figure 2). It is the dominant Late Pre-Contact type found at the McFate Phase village (36CW1) and sites like it located in the French Creek drainage of Crawford County, Pennsylvania (Figure 3). McFate Incised was initially categorized as a “tentative pottery type” with traits shared with the Monongahela Culture of southwestern Pennsylvania (Mayer-Oakes 1955;200).

|

Figure 3. Harry Schoff’s Works

Progress Administration map of the McFate site excavations

Collections of The State

Museum of Pennsylvania |

Further south, McFate Incised is a minority pottery type at the Johnston village (36IN2) site in Indiana County. A more detailed description of the type, although still tentatively defined, was provided by Don Dragoo (1955) based on his investigations at that site where numerous sherds and a vertical compound vessel of the McFate Incised type (Figure 4) were recovered. A formal description of McFate Incised and regionally related Late Pre-Contact pottery types was later provided (Johnson 1994).

|

Figure 4. Vertical compound vessel of McFate Incised (Image

courtesy of Pennsylvania Archaeology Inc.) |

McFate Incised pottery is also a Late Pre-Contact period pottery type reported from the Wilson Shutes (36CW5) site, the three-dimensional earth ring sites in Elk County (Smith and Herbstritt 1976) and numerous rock shelter and small open-air camp sites linking Indian trails (Myers 1997; 2001) and the Smith village site (Lounsberry 1997) in Allegheny County, New York. Monongahela culture sites in western Pennsylvania that have also yielded small quantities of McFate Incised pottery include the Squirrel Hill (36WM35) site in Westmoreland County (Robson 1958) and the McJunkin (36AL17) site in Allegheny County.

Conemaugh Cord-Impressed, always a minority type that is frequently associated with McFate Incised from Johnston phase Monongahela sites (dated circa 1450-1600) according to Johnson and Means (2020: Figure 10.8) is a pottery type characterized by substituting cord-impressed patterns of horizontal and/or oblique decorations made with a tightly spun fiber cord vs. line incising directly applied to the pot’s surface (Figure 5).

|

| Figure 5. Decorative motifs of Conemaugh Corded (After Lantz and Johnson 2020: Figure 12.10) |

Chautauqua Cordmarked and Chautauqua Simple-Stamped are pottery types of the Late Pre-Contact period found in northwestern Pennsylvania and regions peripheral to the Upper Ohio Valley. Chautauqua Cordmarked and Chautauqua Simple-Stamped pottery are hallmarks of the Chautauqua Phase, the principal Late Pre-Contact Indigenous occupation located south of Lake Erie and whose core area of influence was centered around Chautauqua and Cattaraugus Counties, New York and Ashtabula County, Ohio. Both types are present at the palisaded hill forts of southwestern New York reported by Dean (2004) and Schock (1974).

|

Figure 6. Chautauqua Cordmarked pot, collections of The

State Museum of Pennsylvania |

Chautauqua Cordmarked (Figure 6) and Chautauqua Simple-Stamped share similar traits regarding the collarless vessel shape and the tempering of freshwater mussel shell, like McFate Incised. However, their surface treatments are distinctly different. The more common type, Chautauqua Cordmarked was finished with a cord wrapped paddle or dowel tool that the potter pressed or rolled onto the pot. Conversely, pots of the Chautauqua Simple-Stamped type were finished with a plain, non-corded paddle or dowel tool leaving a burnished multidirectional grooved surface on the pot (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7. Closeup view of a Simple-Stamped Pot, collections

of The State Museum of Pennsylvania |

These tools were used to create a row of deep rim impressions on both pottery types much in the same fashion as observed on Monongahela Cordmarked pots (Figure 8) of southwestern Pennsylvania.

|

Figure 8. Monongahela Cordmarked rimsherds (Mayer-Oakes

1955: Plate 115) |

The Late Pre-Contact pottery types described in this blog were primarily used to store, cook or otherwise process food for human consumption, as many of the pots show the clear presence of use wear, damaged rims and burnt food residues adhering to their surfaces. We hope that you have enjoyed reading about the Native American Late Pre-Contact pottery types from western Pennsylvania and the unique traits of the potter’s skills in making them.

References

Carpenter, Edmund S.

1949 Wesleyville Site, Erie County. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 19(1-2):17.

Dean, Robert L.

2004 Preliminary report on Data Recovery Investigations at the Livermore-Wright Site (AO1311.00051), Town of Ellington, Chautauqua County, New York. Report prepared by Heritage Preservation & Interpretation, Inc., Steamburg, New York.

Dragoo, Don W.

1955 Excavations at the Johnston Site. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 25(2):85-141.

Johnson, William C.

1994 McFate Incised, Conemaugh Cord-Impressed, Chautauqua Simple-Stamped. And Chautauqua Cordmarked: Type Definitions, Refinements, and Preliminary Observations on their Origins and Distributions. Paper presented at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Lantz, Stanley W. and William C. Johnson

2020 The Late Woodland Period in the Glaciated and Unglaciated Appalachian Plateaus Province of Northwestern Pennsylvania, Chapter 12 In: The Archaeology of Native Americans in Pennsylvania Volume 2. Edited by Kurt W. Carr, Christopher A. Bergman, Christina B. Rieth, Bernard K. Means, and Roger W. Moeller with Elizabeth Wagner as Associate Editor. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Lounsberry, Kelly M.

1997 The Smith Site: The Chautauqua-McFate Culture in the Upper Allegheny River Valley in Southwestern New York. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 67(1):21-34.

Mayer-Oakes, William J.

1955 Prehistory of the Upper Ohio Valley: An Introductory Archaeological Study. Anthropological Series No.2. Annals of the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh.

Myers Andrew J.

1997 An Examination of Late Prehistoric McFate Trail Locations. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 67(1):45-53.

2001 An Examination of Ceramics from the Dutch Hill Rock Shelter: A Late Woodland/Late Prehistoric Base Camp Located in the Upper Clarion River Drainage of Western Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 71(1):43-68.

Robson, John

1958 A Comparison of Artifacts from the Indian Villages Quemahoning and Squirrel Hill. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 28(3-4):112-126.

Schock, Jack M.

1974 The Chautauqua Phase and Other Late Woodland Sites in Southwestern New York. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Anthropology, State University of New York at Buffalo.

Smith, Ira F. and James T. Herbstritt

1976 Preliminary Investigations of the Prehistoric Earthworks in Elk County, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, William Penn Memorial Museum, Harrisburg.

For more information, visit

PAarchaeology.state.pa.us or the Hall of Anthropology and Archaeology at

The State Museum of Pennsylvania .