|

| Water Street Inn circa 1900 (Pennsylvania State Archives, Ira J. Stouffer Photographs, MG-327, 1915) |

|

Water Street Inn site in 1991 (Heberling 2015) |

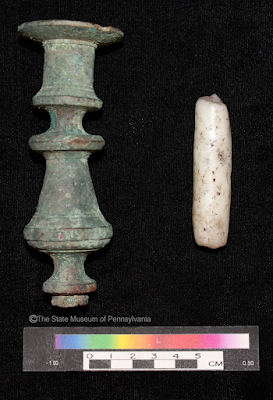

Archaeologists recovered this copper alloy candlestick during their investigation. It is identified as a socket candlestick due to the socket or pocket, where the candle is placed. The holder has an out-turned rim, a hollow shaft, and a short, broken tube on the bottom that would have fit into the missing base (Hume 1969, Geake 2019). This candlestick’s period of manufacture began during the late 16th century and continued through the 18th century (Geake 2019). Since this candlestick was found on a 19th century site, it may have been a family heirloom that had been passed down through generations and ended up at this inn. In the 17th century the popular sport of candle jumping, a game where young girls would jump over a lit candle trying not to put out the flame, was another use for candlesticks (González and Hatch 2019). Perhaps this candlestick and the game had been passed down through a family to one of the young girls that had attended the boarding school located in the former Water Street Inn.

|

Candlestick and

candle fragment from Water Street Inn Collection (36Hu151), The State Museum of

Pennsylvania |

When the inn and tavern were constructed, there was no electricity, and the main light source for rooms would have been candlelight or oil lamps. Along with the candlestick holder a section of a white tapered candle was also recovered from the site. The wick is missing from the candle, but the hole where it once existed remains. Wax candles have been made for centuries, but major developments in candle making occurred in the 1820s when French chemist, Michel Chevreul discovered how to extract stearic acid from animal fats, creating stearic wax. Joseph Morgan developed a machine that permitted continuous production of molded candles in 1834, making candles more affordable and less laborious to produce. By the mid-1850s paraffin wax was first produced, which then led to the mix of paraffin wax and stearic acid for a higher burning point, resulting in a much stronger and odorless burning candle (National Candle Association 2020). The candle found at the Water Street Inn site is most likely a 19th or 20th century molded candle.

View additional candlesticks in the collections from The Pennsylvania

Historical and Museum Commission.

References:

Geake, Helen

2019 Finds Recording Guides: Candle holders. The

British Museum. Electronic document, https://finds.org.uk/counties/findsrecordingguides/candle-holders/,

accessed December 15, 2021.

González, Kerry

S. and Brad Hatch

2019 It Was Colonel Weedon With a Candlestick

on Sophia Street: Another “Clue” to Fredericksburg’s Past. Electronic document,

http://www.dovetailcrg.com/colonel-weedon-candlestick-sophia-street-another-clue-fredericksburgs-past,

accessed December 15, 2021.

Heberling,

Scott D., Brenda Carr, and Patti L. Byra

2015 Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery

Water Street Inn Site (36Hu151), Prepared for Pennsylvania Department of

Transportation Engineering District 9-0 and the Federal Highway Administration.

Heberling Associates, Alexandria, PA.

Hume, Ivor Noel

1969

A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. University of Pennsylvania Press,

Philadelphia (reprint)

Leiser, Amy

2015 History of the Pennsylvania Christmas Tree.

Monroe County Historical Association. Electronic document, https://www.monroehistorical.org/articles_files/2015_1227_december.html,

accessed December 14, 2021.

National Candle

Association

2020 History. Electronic document, https://candles.org/history/, accessed December 15, 2021