October is Archaeology Month and to celebrate, The State Museum of

Pennsylvania announces its annual ‘Workshops in Archaeology’ conference to be

held on Oct. 30, 2021. Due to concerns with COVID-19, this will be a virtual

only event, registration is required. The topic of the Workshops this year

is Hidden Stories: Uncovering African American History through Archaeology

and Community Engagement. To learn more please review our previous blog

post and register for this event on our web page http://statemuseumpa.org/WorkshopsinArchaeology

For additional

programming please visit the Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology, the Pennsylvania

Archaeological Council and the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum .

The

Most Common Artifact Recovered from Precontact Archaeological Sites - Let’s Get

Flakey

A basic guide to stone or lithic flake terminology.

What is the most common artifact recovered from Precontact archaeological sites? Not arrowheads or spear points or pottery sherds that get all of the attention, but flakes – the unmodified and unused by-product of chipped stone tool production. Also known as chips, detritus, spawls, shatter or over the past twenty years, most commonly labeled as debitage, these artifacts are ubiquitous at Precontact sites. They outnumber the tools by at least 100 to 1. Flakes are usually the first artifacts that are found during site surveys, and sometimes the only evidence of a Precontact occupation but they are frequently overlooked during analysis and usually lumped together as a single artifact type. Flakes are not pretty; they usually appear as relatively small slivers of rock and even the larger pieces are not readily recognizable as artifacts to the untrained eye. For a long period in archaeological research, flakes were not thought to be very useful in interpretating past cultural behavior. For example, the early collections in The State Museum of Pennsylvania from the 1920s and 1930s contain more projectile points, pottery and bone objects than flakes. Up until the 1970s, some professional archaeologists did not bother to curate flakes during otherwise systematically excavated site investigations but tossed them in the trash at the end of the day. “Flakes tell us Native Americans made stone tools – so what!”

Based

on flint knapping experiments beginning in the 1960s, (Crabtree 1972) and

becoming common in the 1980s (Callahan 1979), the interest in debitage and the

potential contributions to the interpretation of past cultural behavior became

more common. Now, the analysis of debitage is usually a regular part of

archaeological survey and site reports. These artifacts tell a great deal about

the activities at sites and the tools that were being made and as John

Whittaker (1994:21) observes, the occupants of a site were “so inconsiderate as

to take the useful tools away” so in many cases the flakes are the only

evidence to interpret the past.

|

| Typical core and flake (image from Whittaker 1994) |

The

literature is now voluminous, and the following will serve as an introductory

or basic guide to the terminology used in describing flakes and the analysis of

debitage. All flakes are not the same, but they share certain characteristics. Let’s

begin with some terminology. The block of stone to be hit is called the core

(to the left in the above illustration) and the pieces that fly off are the flakes

(to right). Basically, when a hammerstone hits the edge of a core, the

force of the hammer is transmitted into the core; energy is most pronounced at

the point of impact and gradually dissipates outwardly to the distal end of the

flake. The interior surface of the flake, facing the core is the ventral

surface. The exterior side of the flake facing out is called the dorsal

surface. At or just below the point of percussion, also known as the

striking platform, there is a swelling on the ventral surface known as

the bulb of percussion. Further down the ventral surface of the flake

are ripple marks. On the dorsal surface there are flake scars

where previous flakes were removed from the core. These are characteristics

found on stone that was broken for stone tool production; they are not commonly

found on stone that broke through natural processes.

|

A microcore for the production of razor-like

blades (Photo from the Section of Archaeology,

The State Museum of Pennsylvania)

|

Image

of a flake illustrating the point of percussion or striking platform, the bulb

of percussion, ripples and exterior flake scars. (Image from Whittaker 1994) |

In

a sense, making stone tools is comparable to a wood carver whittling wood. It

is a subtractive process, beginning with an amorphous shaped natural block of

stone and ending with a finished tool. The process of making stone tools is

called knapping or more commonly, flint knapping. Knappers use a stone

where it is possible to predict the manner in which it breaks. Just as

important, knappers must be able to control the break so that tools can be

shaped. The characteristics of the lithic material typically used to make

chipped stone tools, also known as “toolstone”, is that they are relatively

hard, brittle, plastic and homogeneous, containing few impurities. This type of

stone breaks with a conchoidal fracture (cone shaped) similar to a bee

bee shot through a windowpane. Flakes usually exhibit a subtle curve in one or

more directions. In Pennsylvania the most common lithic materials used in the

production of chipped stone tools are chert, jasper, quartz, quartzite,

argillite and metarhyolite.

Knapping

usually requires three different types of tools to break the stone - two types

of hammers and a pointed piece of antler. An abrading stone is used to prepare

and shape the striking platform so that flakes can be more easily and precisely

removed. The hard hammer is for breaking up the blocks of stone from the

quarry into manageable blanks. These may range in size from a baseball to a

bowling ball weighing ten pounds or more. A soft hammer or baton is

usually made from antler (moose or elk) or hard wood (ash or hickory) measuring

less than a foot in length. These are for thinning the blanks into nearly

finished pieces. The final sharpening and shaping is usually performed with a pressure

flaker, commonly made from antler. The point of the antler is placed on the

edge of the tool and small flakes are pressed off rather than struck. This is

the most precise technique of flake removal.

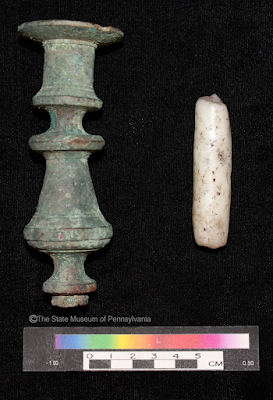

Flint knapping tools (Photo

from the Section of Archaeology, The State Museum of Pennsylvania)

Using a hammerstone on a large flake with other

knapping tools in foreground (Photo from the Section of Archaeology, The State

Museum of Pennsylvania)

Pressure

flaking using a pointed antler. (Image from Whittaker 1994)

Pressure flaking the base of a spear point (Photo from

the Section of Archaeology, The State Museum of Pennsylvania)

The key to the analysis of debitage is that the hammerstone, the baton and the pressure flaker all produce different shapes of flakes and therefore the different technological activities can generally be identified. Hammerstone flakes are relatively thick and especially the bulb of percussion is pronounced. Hammerstone flakes are generally produced during the initial stages of tool production, so they have fewer flake scars on their dorsal surface and even less evidence of previous flaking and grinding on the striking platform. Baton flakes are relatively thin, and the bulb of percussion is diffused as the percussion blow spreads out evenly below the striking platform. There are usually many flake scars on the dorsal surface coming from multiple directions and the striking platform shows evidence of grinding and pressure flaking so the flake can be removed more precisely. In addition, when working a biface (a biface is worked on both flat surfaces of the stone), such as a knife or spear points, baton flakes frequently exhibit a distinctive lip on the striking platform. This is a remanent product of the tool edge that offers evidence of the thickness and size of the tool. Pressure flakes are smaller, usually less than ¾ of an inch in length and thin, often with parallel sides and the striking platform

is usually more heavily ground for better attachment.

|

A

baton flake illustrating the lip on the platform, the diffuse bulb and numerous

flake scars. (Image from Whittaker 1994)

Complicating

the analysis of debitage is that less than half of the flakes are normally complete;

most are broken in some fashion and therefore the striking platform or bulb of percussion

is missing, something not very useful in the analysis of debitage. In addition,

these characteristics or attributes are somewhat subjective, and identifying

these traits is very time consuming. However, when applied to large

collections, the attribute analysis of debitage can be useful in distinguishing

different kinds of knapping activities at a site. Identifying the location of

early stone tool production, the location of actual tool production areas, the

final sharpening and shaping of tools, and the resharpening of tools can be

valuable information in the interpretation of activities at a site.

There

are other types of flakes that define more specific technological activities

such as blade flakes, biface thinning flakes, overshot flakes, bipolar flakes,

and platform rejuvenation flakes and these can be the topic of future blogs.

The foregoing methodology is based on the identification of specific attributes on flakes. Especially, as large state and federal projects in compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act became more common, archaeologists became more concerned with the accuracy of the attribute analysis but also the time involved in flake

analysis. In response, a variety of alternative methods have been developed.

Generally, these fall under the term aggregate analysis and involve

sorting flakes by size using a series of graduated sieves (screens). Needless

to say, these other methods are complicated and there is not sufficient space

to describe them all here. Spoiler alert, it is generally agreed that the best

results are achieved using a combination of attribute analysis and aggregate

analysis (Hall and Larson 2004).

As

noted by Jeffery Rasic, considering the high frequency of flakes at sites, they

are “one of the primary sources of information about human behavior … being

able to reconstruction technological behaviors related to production, use,

transport, and maintenance of stone tools … these data and interpretations, in

turn can shed light on questions of broader anthropological concern such as the

ways people organize their work, subsistence activities, travels, and social

and political behavior” (Rasic 2004:114). Many studies have demonstrated that

debitage at sites changes during different time periods suggesting that

debitage reflects the basic characteristics of the cultural adaptation (Parry

1994).

We

hope you have enjoyed this brief overview of debitage terminology and more

carefully examine the next flake you find realizing that it has an interesting story

to tell. Please visit our gallery at The State Museum of Pennsylvania to see

examples of stone tool production by the Indigenous peoples who developed and

perfected this technology. We also

invite you to visit our on-line collections.

References

Callahan, Errett

1979 The

Basics of Biface Knapping in the Eastern Fluted Point Tradition: A Manual for

Flintknappers and Lithic Analysts. Archaeology

of Eastern North America 7:1-180.

Crabtree,

Don E.

1972 An

Introduction to Flintworking. Occasional Papers no. 28. Pocatello: Idaho

State University Museum.

Hall, Christopher T. and Mary Lou Larson

2004 Aggregate Analysis in Chipped

Stone. The

University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Parry, William

1994 Prismatic Blade

Technologies in North America. In The Organization of North American

Prehistoric Chipped Stone Tool Technologies, edited by P. J. Carr, pp.

87-98. Archaeological Series No. 7, International Monographs in Prehistory, Ann

Arbor.

Rasic, Jeffrey T.

2004 Debitage

Taphonomy. In Aggregate Analysis in Chipped Stone, edited by Christopher

T. Hall and Mary Lou Larson, pp. 112-135. The

University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Whittaker, John C.

1994 Flintknapping: Making and Understanding

Stone Tools. University of Texas Press, Austin.

.