We are getting close to February, which we recognize as Black History Month in the United States and Canada. In honor of African American heritage, we will look at an archaeological site that may be tied to the Underground Railroad. This site is important because typically sites associated with the Underground Railroad are hard to distinguish from the surrounding landscape. For example, often people fleeing their enslavers would be concealed inside a basement or hidden chamber within a house. Any potential artifacts would most likely be mingled with the everyday remains of the family occupying that house, making it difficult to distinguish their relationship.

The site we will be discussing is the Slagle site, 36BD0265, located in West St. Clair Township, Bedford County. The Slagle site was discovered by McCormick Taylor, Inc. during Section 106 survey work for roadway improvements of State Route 56. During these investigations, a site was discovered on the early-19th-century Snook Farm and assigned site number 36BD0217 in the Pennsylvania Archeological Site Survey. The site included both a Precontact lithic reduction component and material culture associated with the 19th and 20th century occupations of the farm.

|

View of the Snook Farm and site 36BD0217 under excavation (Photo Courtesy of McCormick Taylor, Inc.)

The Snook Farm site was determined to be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and because the site was to be destroyed for the planned road improvements, a Phase III data recovery was undertaken. Approximately 2,000 Native American artifacts were recovered from the site, including projectile points from the Archaic Period (3,800 to 10,000 years ago) and chipping debris, biproducts from the manufacture of stone tools.

Further

investigations of the larger Snook Farm property identified the Slagle site

(36BD0265), which was located on a slope to the south of the farmhouse in an

area of large boulders. The site consisted of a scatter of Precontact lithic

artifacts from the Archaic Period (4300-10000 years ago) and oddly, a light

scatter of historic artifacts. The historic artifacts seemed to be out of place

due to their location within the area of boulders and at a distance upslope overlooking

the farmhouse and road. Further research revealed that the farm was used as a

stop on the Underground Railroad around 1849-50 and indicated that this scatter

of artifacts could be related to this use of the site.

|

View

of the slope near the Snook Farmhouse (Photo Courtesy of McCormick Taylor,

Inc.)

The owners of the Snook Farm in the mid-19th century were Amos and Sophia Penrose, Quaker farmers and abolitionists who were active in the Underground Railroad. Joseph Penrose was a young boy when he first saw his family working to help people fleeing slavery. He recalled in a 1904 letter that his grandfather Amos Penrose’s farm was the first station on the Underground Railroad, approximately 10 miles north of Bedford. These people were hidden “in a lonely place in the rocks on my grandfather’s farm” where they would be given meals and kept until it was safe to move on to the next station on the road to freedom in Canada.

|

Portion

of the Joseph Penrose 1904 letter describing fleeing enslaved people in the

hiding place on his grandfather’s farm (Photo Courtesy of McCormick Taylor,

Inc.)

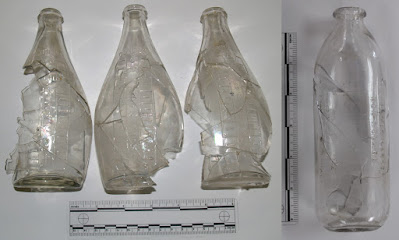

Forty-eight

historic artifacts were recovered from the Slagle site, including domestic

household goods such as stoneware, whiteware, redware, and creamware dish

fragments; a bowl fragment from a smoking pipe; an unknown iron object; a pig’s

tooth; and small fragments of animal bone. It is possible that these artifacts

represent bowls and dishes used for food consumption, meal remains, and

evidence of smoking. Penrose’s letter described visiting the freedom seekers

and his grandfather “giving them their meals” in their hiding place.

|

Artifacts recovered from Site 36BD0265, including stoneware, redware, pearlware, animal bone, and a smoking pipe bowl fragment (photo: PHMC)

Due

to the low number of artifacts, it is unclear if the remains recovered from the

Slagle site were actually used by enslaved people seeking freedom. However,

considering the context with the location of the site and Joseph Penrose’s

letter, this information paints an evocative picture of nervous escaped enslaved

people watching the road from Bedford and praying that nightfall would arrive

before their former enslavers.

The proposed road improvements were altered to preserve the Slagle site so it is possible future archaeologists could discover more information about this important site. Archaeology as a science is constantly improving upon methods for examining artifacts and soils and the potential for new techniques that don’t yet exist or the discovery of written records that would shed more light on the work of the Penrose family.

Further descriptions of the archaeological work and the full letter from Joseph Penrose can be found in PennDOT’s booklet 19th Century Quakers on the Frontier: Archaeological Data Recovery Excavations at the Snook Farm site, 36BD217. (PDF)

If you would like to learn more about efforts to

discover and preserve the archaeological heritage of African Americans in the

mid-Atlantic region, please visit our YouTube videos recorded during our

Workshops in Archaeology 2021, Hidden Stories: Uncovering African American

History Through Archaeology and Community Engagement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JBFESwVOnok

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AwWPPNpK0q8

*Thanks to

PennDOT Engineering District 10-0 and McCormick Taylor, Inc. for assistance

with this blog.

-Look for these other titles in the Byways to the Past

series, some of which can be accessed here: https://www.penndot.gov/ProjectAndPrograms/Cultural%20Resources/StoriesandHighlights/Pages/default.aspx:

At the Sign of the King of Prussia, Richard M. Affleck

Gayman Tavern: A Study of a Canal-Era Tavern in Dauphin

Borough, Jerry A. Clouse

A Bridge to the Past: The Archaeology of the Mansfield

Bridge Site, Robert D. Wall and Hope E. Luhman

Voegtly Church Cemetery: Transformation and Cultural

Change in a Mid-Nineteenth Century Urban Society, Diane Beynon Landers

On the Road: Highways and History in Bedford County,

Scott D. Heberling and William M. Hunter

Industrial Archaeology in the Blacklog Narrows: A Story

of the Juniata Iron Industry, Scott D. Heberling

Connecting People and Places: The Archaeology of

Transportation at Lewistown Narrows, Paul A. Raber

Canal in the Mountains: The Juniata Main Line Canal in

the Lewistown Narrows, Scott D. Heberling

The Walters Business Park Site: Archaeology at the Juniata

Headwaters, David J. Rue, Ph.D.

The Wallis Site: The Archaeology of a Susquehanna River

Floodplain at Liverpool, Pennsylvania, Patricia E. Miller, Ph.D.

Small is Beautiful: Native American Occupations at Site

36MG378, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Andrew Wyatt and Barbara J.

Shaffer

For additional information:

Jaillet-Wentling,

Angela

2019 Archaeology for the People and by the… PennDOT? At

Pennsylvania Historic Preservation Blog,

https://pahistoricpreservation.com/archaeology-penndot/

.

African

American History Month website

2022 African American History Month, https://www.africanamericanhistorymonth.gov/ .

National

Register of Historic Places website

2022 National

Register of Historic Places website for Pennsylvania resources, https://www.nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com/pa/state.html#pickem.