The 1972 Agnes flood affected the lives of thousands of people in the Upper Susquehanna Valley. People perished, personal, commercial, and municipal properties destroyed or otherwise altering the local economies resulted in billions of dollars in lost revenue and cost reconstruction. As well, the removal and redeposition of soils from Agnes’ wrath was destructive to archaeological and historical resources from Sayre to Sunbury and beyond.

|

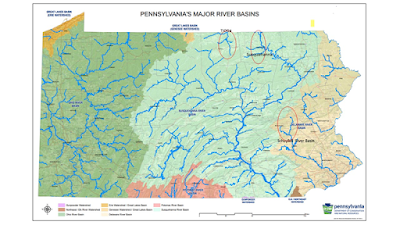

Figure 1. Upper

Susquehanna Valley affected by Agnes |

In early July, only weeks after the 1972 flood, a Native American Indian site was discovered by amateur archaeologists on the Sheshequin Flats located down river from the Sayre/Athens area. The Sheshequin location forms part of a series of sites previously identified in the early 20th century by river expeditions. Historic documents identify the Sheshequin Path which ran from the Lycoming Valley to Towanda Creek as an important foot path developed by the tribes of this region and later utilized by settlers. Historic accounts of the Moravian Mission (1769-1772) located at present-day Ulster, Bradford County recorded evacuation of the village for a few days due to flooding in 1771. The Moravians left the village in 1772 and led a group of followers west to the Allegheny River. Among them were the two sons and a nephew of Teedyuscung, an important Delaware leader and negotiator. The rich cultural heritage of this area was exposed as the result of Agnes’s destruction.

Over a three-week period, the

archaeologists uncovered pottery and clay pipe fragments, stone arrow points

and other prehistoric objects of the Late Woodland period (AD. 900 – AD. 1500).

The artifacts lay on the surface of the flood scoured area adjacent to the active

channel of the Susquehanna River. Concurrently, archaeological remains were

also found by local artifact collectors on Queen Esther’s Flats and on the

broad floodplain formed by Tioga Point at the juncture of the Chemung River and

North Branch Susquehanna River. Diagnostic artifacts from these other sources

were representative of the Late Archaic/Transitional (4000 BCE – 2000 BCE) through

the Late Woodland AD. 900 – AD. 1500) periods.

|

Figure 2.

Susquehannock pot fragment (photo: Smithsonian Institution) |

| ||

Figure 3. Artifacts recovered from the Sheshequin, Queen Esther's Flats, and Tioga Point. Image from the collections of The State Museum of Pennsylvania |

The broad floodplain from Pittston to Nanticoke, Pennsylvania geographically known as the Wyoming Valley, suffered massive inundation and destruction by the flood waters of Agnes. The damage was so severe at the river town of Forty Fort, Luzerne County, that the earthen dike gave way, destroying a cemetery containing many graves. The stone monument erected in memory of the deceased reads:

“On the afternoon of Friday June 23,

1972, the Susquehanna River swollen by the flood waters of unprecedented height

broke through the dike at a point 120 yards south of this site. The swirling

water gouged a four-acre chasm out of the heart of the cemetery displacing

approximately 2500 burials. This park is dedicated by the Forty Fort Cemetery

Association to the memory of those whose gravesites vanished in that singular

catastrophe”

Wilkes Barre was hit hard by

the Agnes flood where the river rose above the 42-foot mark - the impact was

devastating. The Archaeology Laboratory and the artifact storage areas at Kings

College were completely submerged. Water damage to the facility was significant

with the irreparable loss of artifacts and field/lab records from Kings

College’s early archaeological investigations at the Kennedy (36BR0043) and

Friedenshutten sites in Bradford County. Friedenshutten was founded in 1752 as

a Delaware settlement and by 1763, David Zeisberger a Moravian missionary had constructed

a church within the village. The site was home to the Delaware and Shawnee

tribes until it was abandoned in 1772 during removal of the tribes to Ohio.

Several other archaeological sites previously spared by floods located near the town of Plains were wiped out leaving no traces of their presence. After the flood the artifacts housed at the Kings College repository were transferred to Bradford County where they are now under curation at the Wyalusing Valley Museum Association.

|

Figure 4.

Wilkes/King's College during the Agnes flood of 1972 (photo: Wilkes.edu) |

|

| Figure 5. Before and after images of the King's College archaeology laboratory due to flooding caused by Agnes. Image credit: D. Leonard Corgan Library |

The archaeological sites impacted by the Agnes Flood south of the Wyoming Valley on the floodplain of the North Branch are not well documented beyond the information derived from first - hand accounts of surface collectors. Numerous archaeological sites near Northumberland, Pennsylvania were also inundated. The Central Builders site(36NB0117) located a short distance south from Danville, Pennsylvania was one of the sites frequently hunted by artifact collectors. There, stone projectile points affiliated with the Early Archaic (9000 BCE) through Late Woodland (AD. 900 – AD. 1500) period were recovered. Years after the Agnes flood ripped through the valley, investigations conducted by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission uncovered a deeply stratified multicomponent archaeological deposit at the Central Builders site demonstrating the importance of such sites containing very old Native American occupations.

|

Figure 6.

Riverbank cut at Central Builder's site showing stratigraphic deposits from flooding. |

|

| Figure 7. Early Archaic Kirk projectile point found in situ at the Central Builder's site(36NB0117). Images from the collections of The State Museum of Pennsylvania |

|

Figure 8. Kirk point from image above after cleaning

and cataloging |

Downstream from the Central Builders site, flood waters scoured and reshaped the river islands between Berwick and Danville. Significant damage caused by flooding at the north end of Packers Island exposed the remains of a Late Woodland site where surface hunters found the remains of pit features, sherds of pottery and stone projectile points.

|

| Figure 9. Ceramic and lithic artifacts from Packer's Island(36NB0075) Image from the collections of The State Museum of Pennsylvania |

Flooding at the confluence of the Susquehanna’s West Branch and North branches created a pooling effect raising the flood stage to a record of 35.80 feet, a record for the Susquehanna River Valley.

This has been the third installment of TWIPA’s blog on the

Agnes flood and archaeological sites in Pennsylvania. Please join us next time

for more on Agnes and its impact on archaeological sites and the discovery of

sites from flood management projects implemented after Agnes. The series will continue through the month of

June and the anniversary of this event. A Learn at Lunchtime with Curator, Janet Johnson will discuss the impact of Agnes on

the cultural resources of the Commonwealth and highlight archaeological sites

explored in this blog series.

References

Delaney, Leslie L., Jr.

1973 Search for Friedenshutten 1772-1972, A

Bicentennial Archaeological and Historical Project Report for Northeastern Pennsylvania,

Cro Woods Publishing, Wyoming, PA

1928 A History of the Indian Villages and

Place Names in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg.

n.d. The

Historical Marker Database, HMdb.org. Forty Fort Cemetery Lost Graves Memorial. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=105296

n.d. Native History of the Wyoming Valley,

Christianity and Colonization, Friedenshutten Mission

https://digitalprojects.scranton.edu

Wallace, Paul A.W.

1965 Indian Paths of Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Harrisburg.