the process and results of water separation at an

archaeological site

Much of what we know about Native

American plant husbandry is the result of many years of specialized

investigation through the archaeological recovery process of separating

carbonized debris from pit soil via water immersion. This process is called

flotation the principal method used by archaeologists and paleo-ethnobotanists

to recover plant parts, especially seeds and other small fragile remains from

archaeological contexts. Through flotation, specimens are recovered, identified

and studied to better understand the subsistence behaviors of the people who

consumed them. Additionally, starch and pollen grains and phytoliths are minute

residues associated with prehistoric diet. Thus, through a careful detailed

study of these plant related components, hidden information is revealed

relating to human diet. On a regional,

level this research has broad implications that have the potential to greatly

enhance our understanding of cultural adaptations and plant use/consumption of

prehistoric native groups who once occupied the Pennsylvania landscape.

various

starch grains from archaeological sites

At first blush growing crops from

weeds may seem a weird concept but cultures around the world have been doing

just that for thousands of years. Take for example the food patterns of early

Meso-American societies where various strains of grass, by way of eco-human

modification and natural selection developed into the primitive form of maize

called tseosinte. Over time this crop food, became the flint and dent varieties

of maize. Along with beans and other Mesoamerican derived plant foods likely spread

into the Mississippi Valley and on to other parts of North America at an early

period where they became valuable food products in the Native American and

Euro-American diet.

squash

phytoliths

Gourds were grown in the central

Mississippi valley around 4500 years ago and gourd rinds dating approximately

to this period have been recovered from archaeological contexts in the central

Susquehanna valley at the Memorial Park Site. Certain weed seeds carefully

selected for their robustness and nutritional qualities were replanted setting

the stages for incipient Eastern North American horticulture. Though

archaeologically unknown or rarely identified for much of Pennsylvania other

weed crops were Amaranthus a.k.a.

pigweed ,Chenopodium a.k.a.

goosefoot, Iva a.k.a. marshelder and Helianthus a.k.a. sun flower among

others.

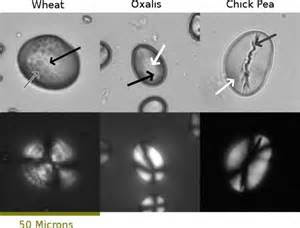

multiple

pollen grains imaged under SEM scope

Horticulture or garden farming

played a significant role in the sustainment of a dependable food base. Climate

fluctuations occurring at certain periods in human prehistory/history, caused

by uncontrollable rises and declines in solar activity, volcanic eruptions and

trade wind temperatures, bore directly on ocean current patterns. Some or all

of these factors were contributory to the Little Ice Age and the Neo-boreal

climatic period between 1350-1850 AD. Their lasting effects were felt in many

parts of the world until the early 19th century when conditions again

improved.

Until the arrival of domesticates with

modifications in the environment human plant food consumption likely did not

change much though some plant foods were only available seasonally. Foods such

as berries and a wide range of nuts only ripened during certain times of the

year (i.e. the fruiting season of summer and the nutting season of late autumn).

In their absence edible parts of soft stemmed plants that emerged in early

spring were processed and eaten along with roots and tubers from mud banks and

wetlands. The latter of which were accessible over much of the year. Some of

these plant products thus harvested were eaten directly or stored for later

consumption added variety to the daily menu of native people.

The appearance of maize (circa 800

AD) and beans (circa 1300 AD) on Pennsylvania’s prehistoric landscape significantly

contributed to changes in Native American demographic patterns. Small

habitation sites grew into large fortified settlements supporting many people.

Surrounding many of these settlements were extensive agricultural fields where

corn, beans and pumpkins were grown. For much of Pennsylvania this subsistence strategy

lasted until the system collapsed and many groups were dispersed in the mid-17th

century when foreign diseases arrived and Europeans focused their economic

pursuits on land acquisition and the extraction of native resources. By the

early 17th century elements of the native diet were adopted by

European immigrants and their presence can still be seen on the modern day

dinner plate.

This has been a brief introduction on the use

of plant foods in the Keystone State from “weed seeds to garden seeds”. The 2015

Annual Workshops in Archaeology Program is only a week away. This year’s theme

is a topic of wide interest to many Pennsylvanians beyond the archaeo-botanical

community. Experts with special fields of interest will be presenting and you

can view the program by clicking on the program banner to the right at the top of this post. We hope

to see you at the workshops on November 14th.

No comments:

Post a Comment