This week in Pennsylvania

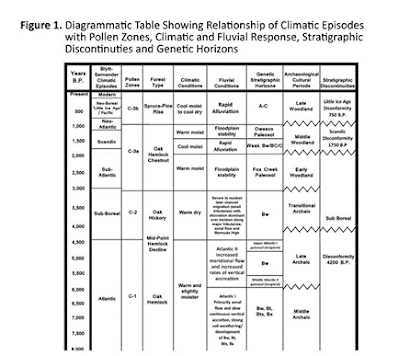

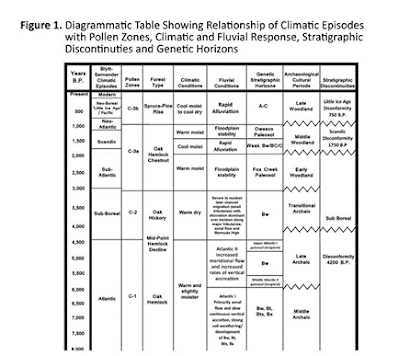

Archaeology (TWIPA) continues with updates from the Fred Veigh donation. Veigh’s

recently cataloged site, Beck’s Hilltop (36WH0647) from Washington County will

aid us in examining a southern regional cultural phenomenon in the Upper Ohio

Valley. Referred to as the Panhandle Archaic complex (Mayer-Oakes 1955), it

roughly dates to 3000-5000 years ago during the Mid-Holocene. It spans the tail

end of the Atlantic climatic episode characterized by a warm moist environment

with relatively stable meandering river conditions by 6000 BP (Vento et al.

2020). Late Archaic hunter-gatherer groups were well adapted to the temperate

forest conditions throughout Pennsylvania by these times. Social adaptations to

higher population levels and predictable food sources are reflected in the

archaeological record by greater regionalization of projectile point types and

diversity of tools used to exploit riverine and upland resources, frequent site

re-use, and range of site size and function. In other words, larger extended

family groups and potentially inter-family groups (bands) began gathering in

predictable seasonal patterns, primarily in river valleys to use seasonally

available resources more intensively. Examples include spawning fish in the

spring and freshwater mollusks at low river levels and ripening wild fruit, grains,

and nuts in the late summer/fall. Panhandle Archaic people returned to smaller

family groups, microbands, in the winter and times of leaner resource

availability.

|

Adapted From: (Vento et al. 2020:

Figure 1.1 (20)). |

There was a climatic shift around

4300 yrs ago, called the Sub-Boreal. A warm dry climate that led to higher

instances of drought punctuated by severe storms and floods. In the eastern regions

of Pennsylvania, archaeologists refer to this time as the Transitional Period (2700-4300

yrs ago), defined by the presence of broadspear projectile points and steatite

bowl fragments. This corresponds with an overall intensification of Late

Archaic hunter-gatherer lifeways expressed as larger semi-permanent to near-permanent

base camps in riverine settings from the spring through fall, then into family hunting

groups in the winter. While some traditionally diagnostic Transitional sites were

present in western, Pennsylvania, they are rare comparatively speaking. (Vento

et al. 2020; Cowin and Neusius 2020; Carr and Moeller 2015; Carr et al. 2020)

The Panhandle Archaic complex was

originally defined by archaeologist William J. Mayer-Oakes in the 1950s based

on artifacts recovered from non-systematic vocational excavations at East Steubenville

(46BR31), and other investigations at shell midden sites—Globe Hill (46HK34-1),

New Cumberland (46HK1), and Half Moon (46BK29)—on the Ohio River in northern

West Virginia. At these sites, the basic pH level of calcium carbonate in large

deposits of mussel shell waste neutralized acidic soils, preserving bone

artifacts and dietary remains generally lost in the archaeological record.

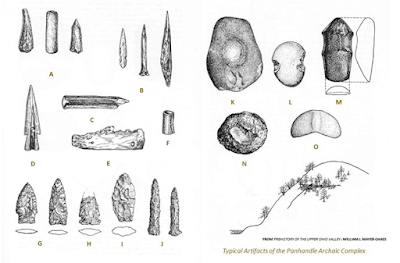

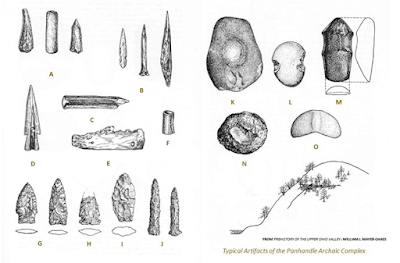

Mayer-Oakes characterized the Panhandle Archaic complex by a series of

diagnostic artifacts including Steubenville lanceolate and stemmed projectile

points, three-quarter grooved round poll and pointed-poll adzes, crescent-shaped

bannerstones, and stemmed bone points. Other artifacts associated with the

complex, but noted as not necessarily diagnostic, were Brewerton-like side-notched

projectile points, straight and expanded-base drills, plain adzes, and bone and

antler tools (Mayer-Oakes, 1955).

|

A- Antler drifts, B- Bone notched,

joint end and splinter awls, C- Bone perforated awl, D- Bone perforated stemmed

point or harpoon, E- Cut, polished and perforated bear jaw, F- Bird bone bead,

G- Steubenville stemmed and lanceolate projectile points, H- Side-notched

projectile point, I- Steubenville lanceolate knife, J- Straight and expanded

base drills, K- Bi-pitted hammerstone, L- Notched pebble net sinker, M- Pointed-poll

adze, N- Core chopper, O- crescent bannerstone. Adapted From: (Carr and Moeller

2015: (101)) |

In the subsequent seventy years

of the Upper Ohio Valley, greater regional surface surveys in southwestern

Pennsylvania, northern West Virginia, and eastern Ohio have documented

Steubenville points and knives from a variety of topographical settings that were

not always associated with shell middens. These include upland sites and floodplain

bottomlands, as well as the high riverine terraces generally associated with the

first identified shell midden sites (Lothrop 2007; Cowin and Neusius 2020; Tippins

2020). These settlement patterns paint a broader picture of territorial range, group

mobility, and provides some insight into subsistence and other targeted

resource activities, like repeat visits to known stone quarry sources for Ten

Mile, Uniontown, Loyalhanna, and Monongahela chert in southwestern Pennsylvania

(Carr et al 2022).

|

Map of the Lithic Quarries Reported

in Pennsylvania and Major Quarries in Adjacent States. From (Carr et al. 2020:

Figure 1.3 (6)) |

However, large scale data

recovery projects conducted in the last thirty years have deepened our

understanding of Late Archaic and Transitional lifeways in the Upper Ohio River

Basin. Absolute dates obtained from undisturbed contexts, data regarding diet,

subsistence, technology, seasonal mobility patterns, and potential insights

into intra and inter-cultural interactions through trade and exchange of

resources and flow of ideas as expressed in material culture are some of the

results of these investigations. This data still constitutes only a handful of Panhandle

Archaic complex sites, the majority of which are multi-component and/or unstratified.

There is still much research needed to better understand the Late Archaic

lifeways of this region. (Carr et al. 2020; Cowin and Neusius 2020; Lothrop

2007).

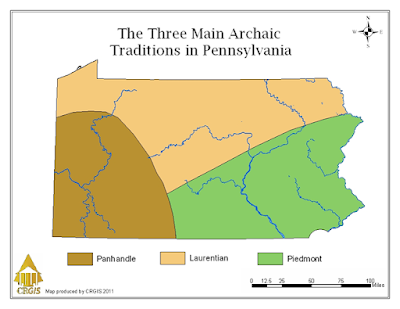

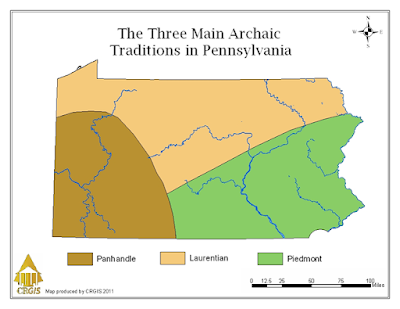

Considering the distribution of

Steubenville projectile points and knives in isolation, the map below depicts

the range of Panhandle Archaic influence in western Pennsylvania, with the

highest concentration of sites on the Ohio, Allegheny and Monongahela drainage systems

in Beaver, Allegheny, Greene, and Washington Counties.

|

Distinctive Projectile Points Define the

Piedmont, Laurentian, and Panhandle Archaic Traditions. From: Carr and Moeller

2015: (91) |

Many archaeologists still

classify the Panhandle Archaic complex as a terminal Late Archaic cultural

development, influenced by the Green River Archaic complex of the Middle Ohio

Valley, west-central Kentucky. Others interpret Steubenville/Panhandle Archaic complex

sites dating between 3000-4300 years ago as a local and culturally distinct expression

of early Transitional Period riverine adaptations in the Upper Ohio Valley (Cowin

and Neusius 2020). In some ways both ideas

are true. Steubenville sites are often chronologically contemporaneous with

traditionally defined early Transitional sites found in other regions of Pennsylvania,

as well as showing some material culture similarities with the Green River complex

shell midden sites in Kentucky. Yet the Panhandle Archaic Complex remains a

distinctly local development of the southern Upper Ohio Valley.

Final analysis of the GAI Consultants data

recovery at the East Steubenville and adjacent Highland Hills site (46BR60)

contained overlapping Brewerton (5680-5210 BP) and Steubenville (4150-3725 BP)

components. Lothrop (2007) characterized East Steubenville, as a recurrent

visited habitation site where small family or extended family groups visited in

the spring and late summer through fall to fish, hunt deer, process shellfish

and forage for wild fruits, grains, and nuts as part of both the Brewerton and

Steubenville associated seasonal round. Interestingly, overrepresentation of certain

faunal remains, such as fish head and tail as well as the cranial and foot

elements of deer compared to other parts, is evidence of kill site processing for consumption

elsewhere. This speaks to the nature of procuring game for later use and strategic

planning for group mobility. Highland Hills, lacking evidence of shell

processing was defined as a short-term task-focused smaller group occupation.

Lothrop (2004; 2007) contrasts the

less sedentary nature of these sites from the near-permanent shell midden occupations

in the Green River Archaic complex (Marquardt and Watson 1983). While the data is still limited and should

not be determined by the East Steubenville site alone, Panhandle Archaic regional

settlement patterns more closely resemble a smaller scale and more mobile Late

Archaic lifeway, as it is currently understood throughout much of the Upper

Ohio Valley. This is a difference from either the Green River Archaic complex to

the west or contemporaneous broadspear Transitional traditions in Pennsylvania.

Beck’s Hilltop is a multi-component upland site surface collected by

Fred Veigh in the 1970s and ‘80s. Located a hard day or more hike southeast of

East Steubenville near Wylandville, Pennsylvania, it overlooks Little Chartiers

Creek in the Chartiers watershed between the Ohio and Monongahela Rivers. Late Archaic

and Panhandle Archaic complex diagnostic artifacts present in the donation, but

not previously described in the Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey (PASS)

record include: four Late Archaic Brewerton-like notched projectile point and

knife varieties, and seven lanceolate and stemmed, Steubenville projectile

points and knives (3000-4300 yrs ago).

|

| Brewerton-like notched point varieties. Onondaga,

Flint Ridge, and Gull River chert. |

|

Steubenville projectile points and knives. Mixed

quarry and glacial cobble lithic sources. |

Lithic materials range from local sourced Uniontown, Ten Mile, and

Loyalhanna chert; and black and mottled gray secondary glacial cobble chert.

Dates are based on recently radio-carbon dated archaeological contexts in the

region (Carr et al. 2020; Cowin and Neusius, 2020). Additional stemmed and

partial hafted bifaces, and refined biface bases are likely associated with

Steubenville related site activities, however, specific attributes are too

ambiguous to definitively type without further site context.

|

| Late-stage biface fragments made from Ten Mile

chert, in various stages of patination or thermal alteration. |

There

are other artifact types that may also correlate with the Brewerton-like and/or

Steubenville components at Beck’s Hill based on analogous lithic source and

tool manufacture techniques recovered from excavations at East Steubenville

(Lothrop 2004; 2007). These include ground stone tool fragments and spalls used

for woodworking, and dedicated biface chipped stone tools used for animal hide

processing and other tasks made from secondary sourced igneous, metamorphic,

and sedimentary glacial cobbles. The definition of a dedicated biface is a tool

made for an express purpose. The examples pictured below are a drill and

scraper. More frequently, hafted bifacial tools were made by recycling or

retooling projectile points, representing a secondary, rather than a primary

use-life of a tool.

|

Diorite tool bit, metabasalt spall and medial

ground stone fragment |

|

Onondaga chert drill fragment, Onondaga chert square-bit

bifacial scraper- possible retooled stemmed point, Gull River chert square-bit

bifacial scraper |

It is likely that by the end of the Late Archaic and start of the early

Transitional Period, Beck’s Hilltop served as a temporary residential site for

small family groups as part of a structured Panhandle Archaic complex seasonal cycle.

Carr et al. (2015) postulates that upland sites, like Beck’s Hilltop, with a

diverse array of artifacts, served as winter encampments, or as small base

camps for specialized resource exploitation at other times of the year. It may be suggested that these small

kin-groups also joined with others at larger base camps along the Ohio river in

the northern panhandle of West Virginia, Beaver and Allegheny County in

Pennsylvania in the spring, late summer and fall to exploit different subsistence

resources at peak availability.

Examining these archaeological resources contributes to our

understanding of the daily activities and settlement patterns of the Indigenous

peoples who lived here prior to the arrival of Europeans. Colonists adopted many of these procurement

strategies from the Tribes who had refined these seasonal sustainability processes

over time. Many of these hunting, gathering and fishing processes continue to

be employed today. We hope you enjoyed

this summary of the Panhandle Archaic complex and recent documented artifacts

from the Fred Veigh Collection. We invite you back to explore more topics in

Pennsylvania archaeology and invite you to view the on-line collections of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

References and Further Reading

Carr, Kurt W.,

et al. (Editors)

2020 Introduction and The Late Archaic Period.

In: The Archaeology of Native Americans in Pennsylvania, Vol 1: Introduction

and Part 2 Introduction. Eds. Christopher Berman, Christina B. Rieth,

Bernard K. Means, and Roger W. Moeller. Assoc. Ed. Elizabeth Wagner. University

of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Carr, Kurt W.

and Roger W. Moeller

2015 The Archaic Period and The Transitional

Period. In: First Pennsylvanians: The Archaeology of Native Americans in Pennsylvania,

Chapter 4-5. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Cowin, Verna L.

and Sarah W. Neusius

2020 The Late Archaic Period in the Upper Ohio

Drainage Basin. In: The Archaeology of Native Americans in Pennsylvania, Vol

1: Ch 4. Eds. Carr et al. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Lothrop,

Jonathan C.

2007 Panhandle Archaic Americans in the

Upper Ohio Valley: Archaeological Data Recovery at the East Steubenville (46BR31)

and Highland Hills (46BR60) Sites WV Route 2 Follansbee-Werton Road Upgrade

Project Brooke County, West Virginia. State Project No. U250-2-13, Federal

Project NH-002 (300). Submitted to West Virginia Department of Transportation,

division of Highways by GAI Consultants, Inc.

2004 Panhandle Archaic Americans at East

Steubenville: Chronology, Settlement, and Regional Comparisons. Poster

presentation in the symposium “New Light on Panhandle Archaic Americans in the

Upper Ohio Valley: A View from the East Steubenville Site, Northern West

Virginia,” presented at the Society for American Archaeology Meetings, April 2,

2004, Montréal, Canada.

Marquardt,

William H. and Patty Jo Watson

1983 The Shell Mound Archaic

of Western Kentucky. In Archaic Hunters and Gatherers in

the American Midwest, edited by J.L. Phillips and J.A. Brown, pp. 323-337. Academic

Press, New York.

Mayer-Oakes,

William J.

1955 Prehistory of the Upper Ohio Valley: An

Introductory Archaeological Study. Anthropological Series No. 2, Vol. 34.

Annals of Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, PA.

Tippins, William H.

2020 Ohio’s

Lanceolate Maker’s – Part I: Debunking the Late Paleo Lanceolate Myth and

Awakening the Late Archaic Reality. Archaeology of Eastern North America.

Vol. 48:157-191.

.